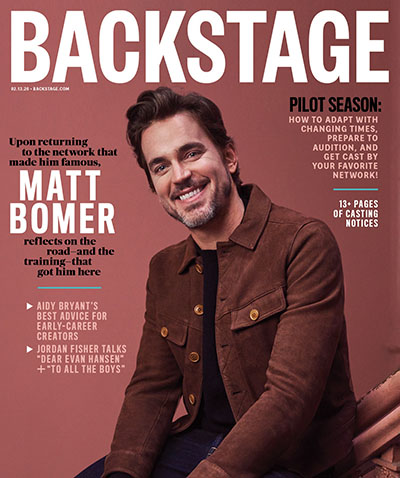

Written by Benjamin Lindsay, this article first appeared in Backstage (Feb. 12, 2020).

Matt Bomer is worried about sending you the wrong message.

Matt Bomer is worried about sending you the wrong message.

The 42-year-old is no stranger to being in front of the camera. He booked his first commercial at 18, was the top-billed star of a hit drama series for six seasons, has been nominated for an Emmy, won a Golden Globe, worked opposite everyone from Channing Tatum to Lady Gaga, and still collaborates regularly with Ryan Murphy. In other words: He’s used to the public eye.

But sit him down on a mid-November evening in New York City’s Financial District and tell him you want to talk about his acting process, from his days at Carnegie Mellon to his upcoming starring role on “The Sinner,” and his usual eager smile and engaged, can-do body language may veil some reluctance. Especially since he’s most often asked about his sexuality and socially engaged projects since he came out as gay in 2012, his family of five with husband and celebrity publicist Simon Halls, and his dedicated (and admirable) health and fitness regimen, to talk candidly about the craft and “all the different actor-y things we do,” he says, feels “esoteric and strange.”

“But,” he interrupts himself, offering a winking acknowledgment to Backstage’s legacy, “I know you’re interested in that, so this is probably the place to do it!” And honestly? Once he buckles in, our interview becomes an hour’s acting lesson that would easily run you a couple hundred dollars at any Midtown studio.

At the root of all of his acting endeavors, Bomer is just looking for the truth. And when the work allows him to run with it, he’s willing—and, at this point in his career, able—to do just about anything it takes to get it right.

This is perhaps most apparent in his commitment to a role’s physical demands. From the sexed-up brawn required of his male stripper in the blockbuster “Magic Mike” and its sequel to the 40 pounds he shed for HBO’s award-winning screen adaptation of Larry Kramer’s HIV/AIDS drama “The Normal Heart,” Bomer physically drags his body that extra mile when given the opportunity and the material.

“On ‘Normal Heart,’ I felt a tremendous responsibility to my community, to all the people who had to suffer through that time, and I thought, Well, if I have to risk my life to do it, to convey that, then it’s worth it to me to tell that story,” he says.

To a lesser but still laudable degree, the current third season of “The Sinner,” produced by UCP, also called for a tangible sacrifice. This photo shoot and interview were booked months before the premiere, because three-quarters of the way through filming the anthological USA Network drama with Bill Pullman and Chris Messina, Bomer was due to make some severe alterations to his appearance that he’d rather not have captured on a magazine cover. (No spoilers, but his diet was limited to 500 calories a day, and he sips a pressed juice for dinner intermittently during our conversation.)

But his role prep is more than skin deep—Bomer employs exacting character work for each of his performances. “The Sinner,” for one, from creator and showrunner Derek Simonds and casting directors Douglas Aibel and Stephanie Holbrook, has him playing Jamie, a beloved teacher at an all-girls private school, a husband, and a soon-to-be father who harbors a dark past. Upon an unexpected reunion with a college friend (Messina), his actions lead to tragic consequences.

“Everything seems to be going his way, but underneath all that, he is suffering from a really profound sense of loneliness and isolation, and that ultimately leads him to a kind of nihilism and terror and, ultimately, violence,” Bomer teases. “He’s having a romance with a philosophy that he doesn’t necessarily have the psychological structure to be able to support in a responsible way.”

It’s a goliath role, one that brings him back to prime time after “White Collar,” the USA Network series that made him famous, and one that Bomer admits he was uneasy about taking on. Then again, it was that questioning gut check that let him know he had to say yes.

“One thing that’s always been a big lure for me is [asking], ‘Am I going to have to get out of my comfort zone to play this part?’ ” he says. “You have opportunities that come your way where you’ve done it before and you know you can do it in a certain way. But certainly with ‘The Sinner,’ I thought, I don’t know how I’m going to do this; I don’t know how I’m going to bring this to life. That scared me—and that’s very appealing. People make entire careers out of just doing what they’re good at, and I respect that. But for some reason, that [fear] is what makes the process exciting to me.”

The first episode alone has his character questioning his reality, toying with self-harm, and losing control of his emotions in the midst of a police interrogation, and it previews the fatal moment that sets his downward spiral into motion. All that is paired, of course, with Bomer’s trademark charm and charisma placed front and center.

So, how did he find his way into such a complex psyche? According to Bomer, praise is due to Simonds for giving him and the rest of the cast the creative tools and time they needed to mine the crime thriller’s material. Especially in television, Bomer says, a rehearsal period like theirs “is unheard of.” Simonds also introduced an all-new creative process for the longtime actor: dream work.

As Bomer explains it, Simonds employed the help of creative dream work coach Kim Gillingham to help the “Sinner” ensemble tap into their subconscious and find authenticity beyond the page.

“Without bastardizing anything, because this is the first time I’ve done it, I’ll try to give you the best [explanation] I can in layman’s terms,” Bomer says. “Basically, you keep a journal near your bed at night, and you ask your psyche—your higher power, whatever—to reveal certain aspects of the character’s experience in a dream that night. For the first few days, nothing was really coming. And then I started to get these hugely archetypal dreams.

“Then, with Kim, you bring the dream to life. You do all these exercises, you drop back into the dream; and from that, you can find gesture, physical aspects of your character, emotions that they might be going through, how the piece parlays to your life and your experience and where you are right now. Often, things from my past will become suddenly relevant to the story.”

Particularly when playing opposite Messina—a man with whom Jamie is meant to have had a close, yearslong relationship on the series—Bomer enthuses that the dream work allowed both of them to “break down so many walls” and to “really lay ourselves bare.” It fostered an understanding and mutual support before getting to set that would otherwise take an entire shoot to accomplish.

“I was really interested in doing dream work because I was interested in not intellectualizing everything and letting creativity bubble up from my subconscious,” he says, adding, “I would recommend it to anyone. It’s a great way to have an experience with the piece.”

Beyond the preparatory dream work (“I only got to do it for maybe the first three or four episodes, because then the workload just got so intense,” he admits), Bomer has more practical bolts of building a character. He’ll often turn to the textbook teachings of Konstantin Stanislavsky, posing, “What from my life could be compared to the circumstance that [this character is] in?” He also cites two influential acting coaches and mentors he trains with in Los Angeles.

“In terms of how I approach every role, one of my main mentors is Larry Moss, and we always work with the given circumstances and then use the ‘as-ifs’ when we need to.” Noted movement teacher Jean-Louis Rodrigue is also in his rotation. “He’s actually an Alexander [Technique] teacher, but he works with all different kinds of physical aspects of character. [We] do a lot of things just to get you out of your head.”

On top of that, Bomer is a lover of note-taking: “I could show you my reams and reams and reams of pages of notes. I’m a homework nerd.” He even keeps a journal titled “My Split Personality Says…” where the left side of the page has the heading “I’m thinking this,” while the right lists “I’m feeling this.” Particularly with a character like Jamie, where how he presents himself may not actually coincide with who he is on the inside, such a simple tool proved invaluable while doing the day-to-day work.

“Even just between scenes, I would jot down what Jamie was thinking and what he was really feeling while they were setting up the camera,” Bomer recalls. “I found that to be a useful exercise, and also a way to kind of maintain some isolation without being rude.”

It’s all a testament to the fact that even 20-plus years into his career—one that he readily admits saw leaner periods of catering, bellhopping, and survival job hustling to make rent—Bomer is continuing to learn, grow, and navigate new parts of himself and his process. Even at the height of his abilities, he’s still looking to better his previous best.

Our conversation eventually takes him back to his first film, the Jodie Foster–starring “Flightplan” in 2005, and one particular lesson gleaned from his days on set. Recalling how the makeup of the set—a literal airplane—allowed for everyone to look on during Foster’s rehearsals, Bomer says that someone advised him point-blank during that downtime to “take every job that’s offered to you.” He’s never forgotten it.

“I’m really glad that woman told me that, because I took her advice and I just started taking, pretty much, whatever gigs came my way,” he says, citing bombed auditions for “Tarzan” on Broadway, his unlikely day player stint on soap opera “Guiding Light,” and his much-reported—but sadly never realized—casting as the Man of Steel.

“You get out of theater school and you start to think, Hmm, I should really be doing ‘Hamlet’ at the Delacorte. And it’s like, ‘Yeah, good luck, kid!’ We don’t all have that charmed existence, you know? So sometimes the best thing you can do is take the job. And no matter what that job is, bring your work ethic, bring your collaboration, be on time, and bring a sense of enthusiasm and commitment and dedication to the work. We can be overly precious, and sometimes it’s good just to make sure you’re exercising your instrument. If it’s an opportunity to work and get paid for it in a production that you feel like you can expand your craft on, do it.”