Written by Valerie Gladstone, this article first appeared in The New York Times (Dec. 16, 2001).

The first thing the actress and playwright Pamela Gien did after she learned that the filming for television of her Off Broadway hit, ”The Syringa Tree,” would start in a week was to call Jean-Louis Rodrigue. He is a popular movement coach in Los Angeles whose specialty is helping actors bring the gracefulness and fluidity of dance to their performances. He had been working with Ms. Gien for three years, and now she wanted a few last-minute pointers.

The first thing the actress and playwright Pamela Gien did after she learned that the filming for television of her Off Broadway hit, ”The Syringa Tree,” would start in a week was to call Jean-Louis Rodrigue. He is a popular movement coach in Los Angeles whose specialty is helping actors bring the gracefulness and fluidity of dance to their performances. He had been working with Ms. Gien for three years, and now she wanted a few last-minute pointers.

In her one-woman autobiographical play, set in South Africa during the 1960’s, she portrays more than 20 characters, ranging from a 6-year-old English schoolgirl to a 60-year-old South African farmer. She was nervous about performing under the close scrutiny of the camera, and Mr. Rodrigue, as he had in the past, calmly dispensed a few tips.

”Remember, Pamela, when you play two characters in a scene, use some of the same gestures,” Mr. Rodrigue told her when they met last month in her Manhattan hotel room. ”If you blend the gestures, the transitions will be more graceful and they’ll appear effortless.”

A combination of acting coach, choreographer and physical therapist, Mr. Rodrigue uses techniques that have much in common with dance training. Dancers are taught to rely on movement and gesture to convey the personalities of characters, an idea he stresses with Ms. Gien. Similarly, he shows her that by employing only a few gestures to define a character, her performance will gain the continuity of a well-constructed dance.

To start off their session, Mr. Rodrigue suggested they run through a section of the play in which a husband and wife argue. Tall and elegant in black slacks and gray blouse, Ms. Gien lowered her voice to sound masculine and weary, sloping her shoulders and raising her hands in a gesture of helplessness. But then as she shifted to the wife, her shoulders rose and her face showed desperation. Mr. Rodrigue stopped her. ”Don’t adjust your posture so radically,” he said. ”You’ll wear yourself out. Just change the tone of your voice slightly and clutch your hands — that’s enough to show that you’ve changed roles.”

Mr. Rodrigue also encouraged her to focus on breathing techniques that would give her the stamina to sustain the 90-minute performance. His teachings emphasize an awareness of the body and the physicality of performance. ”When performers make the physical component of their work as important as the intellectual,” he said, ”they become far more convincing.”

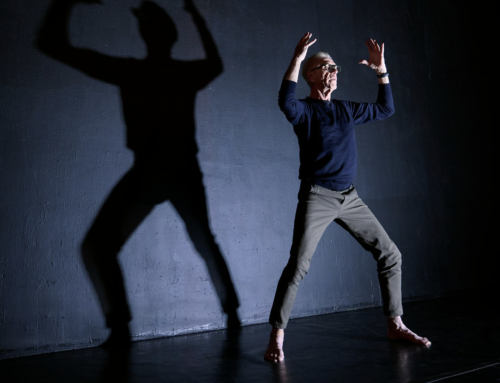

Born in Morocco, raised in Italy and originally an actor himself, Mr. Rodrigue has the lean, muscular look of a dancer. He was inspired to study the body when, as a boy, he saw some of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings in Milan. ”He depicts the body as a place where creation happens and imagination lives,” he said. ”That idea stayed with me.” It also led him to the Alexander Technique, a system for releasing muscular tension named for the Australian actor Frederick Alexander, who developed it in 1904.

He first applied the system to his acting and then turned to teaching full-time in the Department of Theater and Music at the University of California at Los Angeles and consulting for the Verbier Music Festival and Academy in Switzerland. He also has coached members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and acrobats in the Cirque du Soleil.

Mr. Rodrigue’s first goal is to rid an actor’s body of tension. To observe Ms. Gien’s breathing patterns, he had her stretch out on the floor. ”This is how I locate where she’s tense,” Mr. Rodrigue said as he gently pressed his hands on her temples and then on her lower back. ”When you don’t breathe freely,” he said, ”your spine contracts and your lower body loses its flexibility. Pamela needs some work there.”

Ms. Gien’s play will be broadcast on the Trio cable channel in May. Beginning in February she will appear in the role again when her play opens in London. (Kate Blumberg, who replaced Ms. Gien, performs in the current New York production.)

Mr. Rodrigue also specializes in European movement of the 17th and 18th centuries. During that time the Italian and French aristocracies were greatly influenced by classical ballet, which had recently developed in their countries. Consequently the dignified posture and elegance of dance became a sign of breeding and taste.

Years ago, Mr. Rodrigue also trained as a ballet dancer. That background helps explain why the director Charles Shyer asked Mr. Rodrigue to work with the cast of his new period movie, ”The Affair of the Necklace,” which stars Hilary Swank as a countess. ”I didn’t want an academic movie, what the English call ‘wig acting,’ ” Mr. Shyer said. ”I wanted it to be true to the period yet with a contemporary feeling.”

A daunting task. ”I had to transform Hilary, a woman who won an Oscar for playing a man in ‘Boys Don’t Cry,’ ” Mr. Rodrigue said, ”and the actor Simon Baker, a regular guy, a surfer from Australia, who plays her lover, into believable French aristocrats.” Mr. Rodrigue’s familiarity with ballet came in handy. Ballet dancers, he said, are much more accustomed than actors to making quick role changes. And a ballet dancer, he added, might perform as a peasant in ”Giselle” one night and as a cowgirl in Agnes de Mille’s ”Rodeo” the next.

Mr. Rodrigue worked with Ms. Swank in a spacious, high-ceilinged studio in Los Angeles, which he said was intended to suggest the grand salons of Versailles, where some of the film’s action occurs. He also brought in 18th-century costumes and props, like walking sticks, fans, hats, capes and even a tea set, to acclimate the actors to the period. ”I wanted Hilary to know what it felt like for a long period of time to move around in big clothes, with big hair in a big space and delicately serve tea and hold a sugar cube in her spoon,” he said.

Ms. Swank was a willing pupil. ”Jean-Louis taught me that an aristocrat didn’t just sit down in a chair,” she said. ”She floated down. And she floated up and down stairs. She certainly didn’t climb them, for that implies effort.”

Later, while on location in Paris and Prague, the actors would dress up every morning in their costumes to get in more practice before the actual filming. Mr. Rodrigue said that he would bow, and Ms. Swank ”curtsied and I kissed her hand.” As the actors strolled around the set, it wasn’t always easy for them to keep from giggling. ”I grew up poor, in a trailer park,” Ms. Swank said. ”Playing an aristocrat wasn’t second nature.”

Mr. Rodrigue also prepared a videotape that showed the kinds of movements the actors could use to appear authentic in their roles. Mr. Shyer was so impressed with it that he distributed copies to members of the cast.

Mr. Rodrigue was particularly pleased with how a love scene in the movie turned out. A couple, sitting in a theater balcony, try to kiss secretly, shielding themselves from those around them with her fan. ”The timing had to be perfect, with the kiss about to begin as the woman opens the fan and just finishing as she closes it,” he said. ”An underlying rhythm unites the elements.”

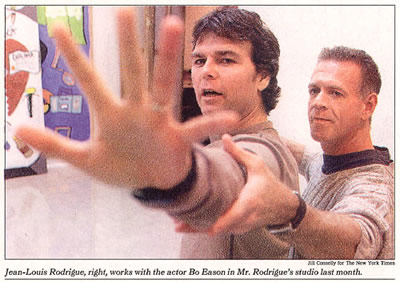

BO EASON, a former free safety for the Houston Oilers football team, is another to have studied with Mr. Rodrigue. For his autobiographical play, ”The Runt of the Litter,” which will open Off Broadway in January, Mr. Eason wanted advice on how to play several characters in his story about a tortured young man. ”I had to learn how to breathe and move all over again,” he said.

Since the hero sets out to destroy his brother, Mr. Rodrigue suggested that Mr. Eason watch National Geographic videos to see how lions moved in preparation for a kill. ”I saw they didn’t waste any movement, and that their focus was absolute,” Mr. Rodrigue said. ”Their lines were as sleek as good dancers.”

Mr. Eason apparently learned his lessons well. When the play opened in Houston last year, a critic, impressed with his gracefulness, compared him to a ballet dancer. ”I don’t know what my ex-teammates would say,” he said, ”but I’m proud.”