Written by Joan Schirle

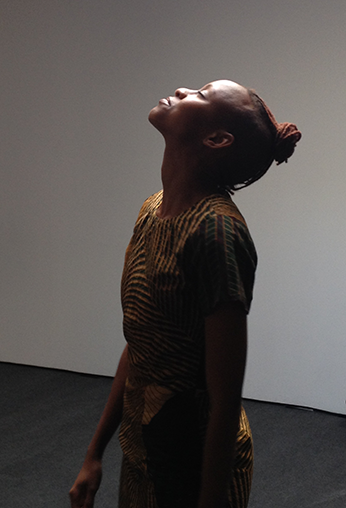

An Alexander Techworks student gracefully illustrates the ease of looking up with no contraction.

The study of voice, music, mime, theatre, and dance places great demands upon the adult body, already developed in habit and structure. And the mind is challenged as well, through the creation of performance material, improvisations, and the accelerated self-discovery which accompanies growth as a performer.

Often, students must unlearn as much as they learn. In her article, Tension and the Actor, Joyce Wodeman writes: “Before I came across the Alexander Technique I used to be aware of bad habits in some of my drama students without understanding what was wrong or what to do about it . . . I mean those deep-seated tensions and constrictions that one sees to be typical of the person’s activity as a whole and of which he is largely unconscious: what in Alexander terminology is summed up as someone’s ‘manner of use.'”

The Alexander Technique is a method of self-discovery which explores the basic impulses of human movement, how we interfere with our own coordination, and, it offers a means to change. Alexander’s method directly addresses basic performance problems:

The student should learn that in whatever he does, however small the gesture he uses, a kind of current, life, must go through the whole body. He will gradually discover that his entire body takes part in the gesture even if it does not move with it . . . All exercises should aim at producing a state of balanced physical well-being, a state of poised relaxation which leads to an agile control of timing. This physical well-being is important to an actor’s imaginative growth and is essential to the development of his means of expression.

This is why, at the Juilliard School, we have added the Alexander Technique to our training of the body. . . a method by which the student can free himself of postural bad habits and become aware of the meeting point of his body and mind. At the same time the Technique corrects the alignment of his body and his coordination in general.

(Michel St. Denis, Training for the Theatre)

Alexander’s own history tells of a young Shakespearean orator and actor whose career in the late 1800’s was threatened by recurring hoarseness. Through a long period of self-observation and work he not only cured his problem but pioneered a whole new way of learning.

In following Alexander’s steps we begin with the detailed observation of the habitual ways we use ourselves in everything we do. Wodeman says, “no amount of ‘showing how’ or instruction imposed from the outside can achieve a desired result as long as a person’s deepest habits are pulling against it.” Though many habits are useful, helping us get though life without pondering every action, habits that limit our choice of movement can develop without our noticing.

Performers are unfortunately encouraged to adopt the habit of ‘end-gaining.’ End-gaining is the term used by Alexander to describe our concern with being right, and with goalskeeping the juggling clubs in the air no matter what, projecting to the balcony, holding the handstand, mastering a difficult instrumental passage, and so on.

We are trained and conditioned to be ‘present’ only in relation to the goal. When I go from my house to the grocer, I’m not present until I’m back at the house. Going from point A to point B we are in a kind of non-life, and from B to C the same. This is one of our earliest lessons. . .to be in relation to the goal. This teaches us to live in ‘absent time.’ (Joseph Chaiken, The Presence of the Actor)

Alexander discovered that performance habits reflect as in a magnifying mirror the habits of everyday activities. ‘Absent time’ on stage is wasted opportunity for creation; but how can we expect performers to eliminate ‘absent time’ on stage unless we train them to do so in the daily life where most of our hours are spent? As Aldous Huxley noted, “An education which allows you to use yourself wrongly is almost valueless.”

Once observation reveals habits we wish to change, the Alexander student learns to prevent these habits in movement and in rest, and to consciously direct the body in lengthening relationship between her head, neck and back that allows the entire organism to function with more ease. Because this direction, or ‘thinking-in-activity,’ works in movement, there is no need to stop activity, close our eyes, or do special exercises, in order to develop good use.

What is good use? “Good use” implies economy and availabilityto the moment, to the partner, to the emotion, to the unexpectedthe essence of improviso and the enemy of rigidity. Good use implies choice in deciding to go into action, what action to do and how to do it. Good use means we are capable of delicacy and subtlety as well as thrust and force. These are qualities of movement that the Alexander student learns to distinguish, since all movementpicking up a pencil, a sprinter’s burst, the exquisite conservation of energy in a resting cat becomes a source of observation and constructive possibilities.

***

Joan Schirle is a Senior Teacher of the FM Alexander Technique and a professional actor. She alternates her roles as Co-Artistic Director of the Dell-Arte Players Company and as a teacher.

Joan Schirle is a Senior Teacher of the FM Alexander Technique and a professional actor. She alternates her roles as Co-Artistic Director of the Dell-Arte Players Company and as a teacher.